Back in the 2020 lockdown, our towns and villages changed. It started with rainbows in people’s windows, painted stones for people to seek out on their daily mandated walk. For Lewis Dobson, working as a care worker at the time, it also sparked a change of direction.

“It started with wanting to paint some walls in Sacriston,” Lewis said. “I was always driving past them; they were in a really bad state, and it seemed like they’d been that way for so long.”

That first attempt was something of a hit and run affair. Neither artist nor owner, a local scrapyard, really knew what to expect. “I painted so quick, and got away,” Lewis recalls. “I didn’t even leave any contact details in case I got into trouble!”

Instead, though, there was encouragement and excitement. Lewis’s work began to appear in other nearby villages – Edmondsley, Witton Gilbert – and gradually a hobby turned into a small business as Durham Spray Paints.

‘We need to be doing really big things’

Coming from a healthcare background, a sudden pivot to street art was something of a surprise. However, Lewis’s experiences of working in the heart of communities and responding to direct feedback from the streets he was decorating persuaded him that art could be an extension of his role in the care sector.

“I was really happy being a care worker, I thought that was my vocation and I was never interested in doing this as a job,” Lewis said. “I always knew I had no interest in painting Minecraft stuff in kids’ bedrooms.

“But the more I interacted with people, I started to realise how I could combine the caring work with the painting. I got really conscious of what my painting can do for people, it just comes together really well.”

Now a big part of Lewis’s work involves reaching into communities, particularly sections of society that feel isolated or neglected by the mainstream.

“This is a really good avenue to approach hard-to-reach people and grab the interest of younger people,” he said. “We are offering some solutions for youngsters, but I don’t think they are radical enough. Plus, there’s a lot less on offer now because of funding cuts and austerity.

“People are doing good things, but I’m interested in a more radical approach because the situation young people are facing in their lives today is actually really serious. We need to be doing really big things in response to that, so I’m just trying to get stuck in.”

Unlike a lot of youth provision, which focuses on developing skills for the employment market, Lewis wants to encourage a more holistic view. He’s committed to helping people develop through creativity, recognising the intangible benefits of art that can’t easily be measured on a balance sheet.

“Art is such a beautiful thing to promote,” he said. “Even though I do this as a job, it’s not about getting people to do something for their CV.

“We can have art for art’s sake. If you pick up a spray can or a brush, whatever, you can just enjoy the process. I feel like that’s the way I’m good at teaching, that’s what I’m passionate about.”

Community connection

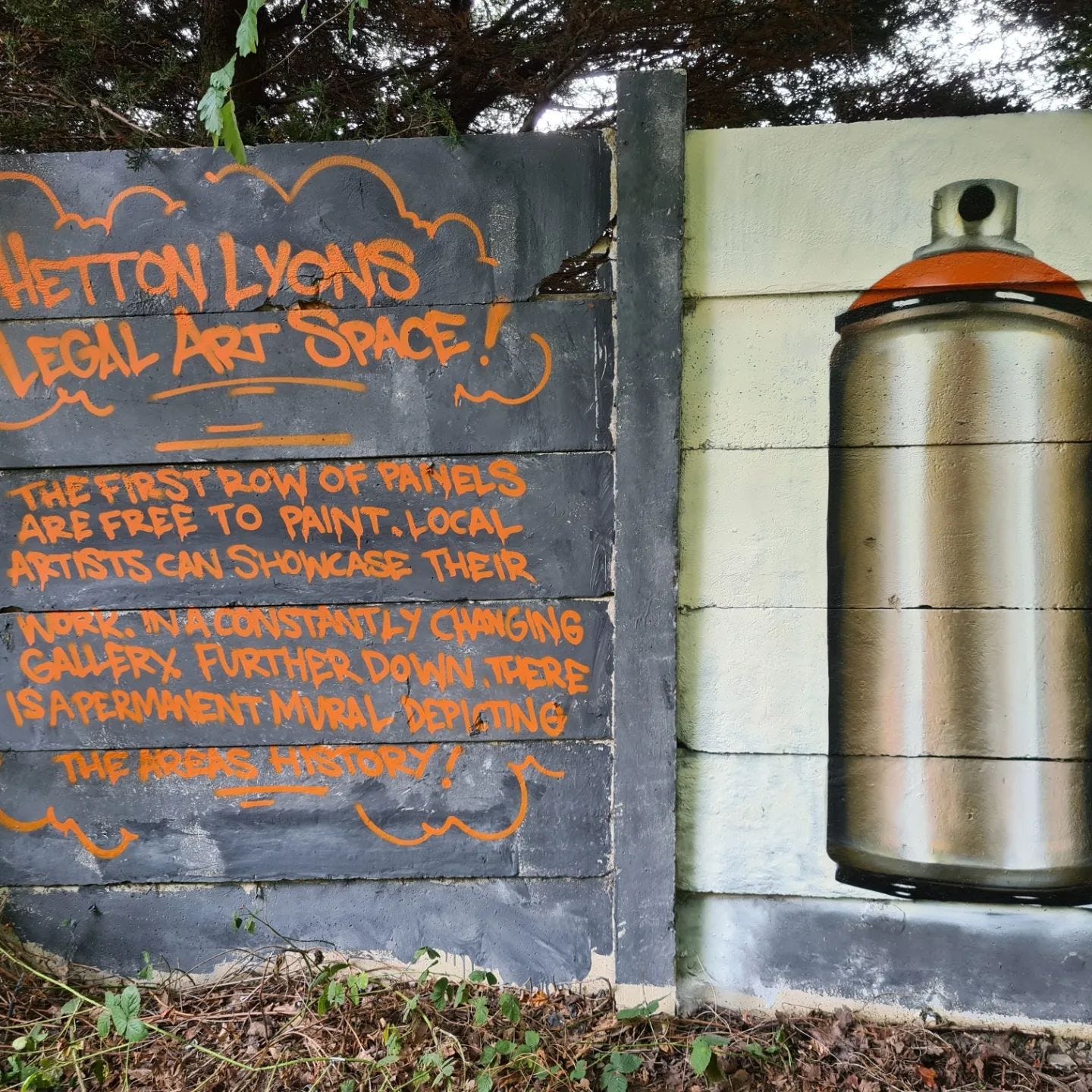

That personal agenda of working with hard-to-reach sections of the community is neatly embodied in a recent project in Hetton. Invited to spruce up an area beset with graffiti, and honour the town’s proud mining and railway heritage, Lewis found a way to incorporate some of what he found on the site. In future, part of the display will include space for everyone to add their own contributions.

“Not everyone would value what was already there as artwork,” Lewis admitted. “In reality, it definitely is. It’s a lot more considered that people often think. Because my background is in street art, I know where they are coming from and I wanted to try to engage with them – and it just worked.

“In the end, it looks really good, and it works for everybody.”

The end result, sponsored by a renewable energy company investing in a nearby wind farm, combines the client’s brief with several themes that resonate with Lewis.

“I was able to incorporate my agenda as well, to engage with hard-to-reach groups and support art for young people. It’s just about talking to the community and trying to get people from different demographics to engage with each other.

“I think I’m getting a reputation as an artist who isn’t just going to come in and paint another picture of a pretty girl or something. I love getting stuck in, chatting to people and learning about an area. I’m very interested in history and the social space of the northeast and I want to reflect that in my work.”

‘You don’t hear artists who sound like us’

Inspiration comes from many sources, but is rooted in a Northeastern identity. One of Lewis’s first murals was a recreation of a self-portrait by Norman Cornish, Spennymoor’s renowned painter of scenes from a mining community.

“To be honest, at the time I’d never really seen his work. I just really liked that portrait,” Lewis said. “Plus, the original was an oil painting and I was interested in trying to represent that technique in spray paint and see how it worked.

“That kind of started me on this idea of our identity in the Northeast, villages that were based around the pit and now they’re not based around anything.”

Cornish’s own story was a powerful guide. “I went to a Norman Cornish exhibition and heard a recording of him speaking with his northern accent. I found it almost shocking, for some reason. You don’t hear artists who sound like us so to hear it was quite emotional.”

Along with the Pitmen Painters in Ashington, Cornish and the other artists who emerged from the Spennymoor Settlement form part of an alternative regional tradition, one of creativity as well as heavy industry.

“I want to tap into that whole idea, the idea that just because you’re from the villages doesn’t mean you can’t be educated. Just because you come from Spennymoor or Bishop, there’s no reason why you can’t be really proud of being an artist.”

A festival of murals

That kind of pride in creativity, and a strong sense of ‘art for art’s sake’ lies behind a festival of murals planned for summer 2023. Again, there’s a strong emphasis on working with the community – but this time with a view to exploring the oft-romanticised industrial heritage of the region.

“In Sacriston, I was really keen to do stuff about the mining industry but when I got talking to people it was clear that Sacriston was one of the worst pits to work in,” Lewis said. “It was like a wet pit, so you were constantly soaking and underground and freezing. “The conditions were absolutely inhumane.

“I really want to celebrate our history but I also want to examine it. I want people to think about the effects of extracting all that coal, what it did to our people and our land, the effect it has on the area. I hope the festival will answer these questions.”

At the same time, this is not intended to be a political event and there is every bit as much emphasis on the future as the past.

“I want to have a lot of community engagement. It’s about going into schools, talking about art, helping kids make a connection between people coming in and talking with them, drawing with them, and going on to make these big paintings.

“I have a few ideas, but I want to hear from other people who are passionate about where they live, where they are from – people who really believe in the project and want it for their area.

“Hopefully there’s going to be a lot of really interesting paintings, bringing some special artists to the Northeast, helping to mentor our own local artists and doing great stuff together.”